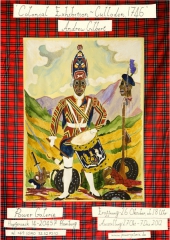

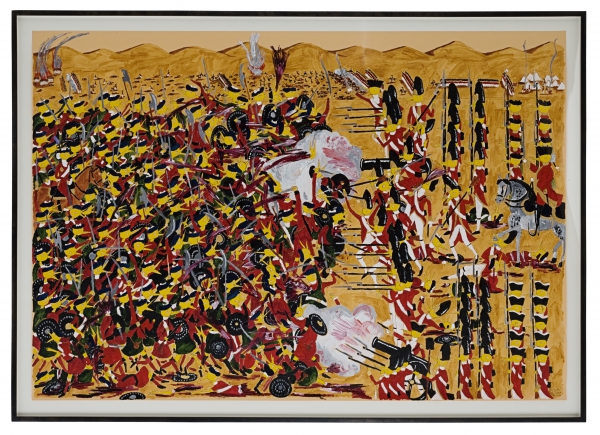

In the “Colonial Exhibition: Culloden 1746” (on show at power galerie, Hamburg, 27 October – 7 December 2012), the Scottish artist Andrew Gilbert presents a tableaux and series of new drawings in the tradition of a military museum, exploring this epic and blood drenched historical event: the last battle fought on British soil. Born 1980 in Edinburgh, Gilbert is truly fascinated by the British soldier of the 18th and 19th century and its appearance in representations of the colonial wars, around which his extensive work circles. Since 2002, Gilbert is living and working in Berlin.

On 16 April 1746, the last chapter of the unsuccessful Second Jacobite Rising was unfolded at the Battle of Culloden: Prince Charles Edward Stuart – better known as “Bonnie Prince Charlie” – and some 5,000 soldiers, mostly Highlanders, fought against some 9,000 loyalist troops (including a significant amoung of Scotsmen and a small number of Hessians from Germany) commanded by Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, some 4.5 miles from Inverness. The Jacobite army was badly equipped, hungry, tired and not the least poorly trained when it met the loyalist troops. The latter opened fire with its far superior artillery. When Charles ordered the charge, only parts of his troops followed: the MacDonalds – who traditionally fought on the right wing – had been positioned on the left wing and, feeling aggrieved, mostly refused to charge. Less than half an hour after the first shot, more than 1,200 Jacobite soldiers had been killed, while the loyalist troops had some 50 fatalities.

The Duke of Cumberland, however, ordered all the wounded and imprisoned Jacobite soldiers to be killed, arguing that they were no prisoners of war, but traitors only. Even more so, he sent British troops to the Highlands on “pacification missions”. They did so with such cruelty that Prince William received his nickname “butcher” and the English-Scottish relations were profoundly damaged. While it was not unusual for these times, it might still be interesting that both leaders were quite young (Charlie was 25 years, while William was short to reaching this age): to what an extent had a sense of responsibility been developed, be it for one’s own soldiers or for the long-lasting consequences of one’s deeds, if not morality in general?

In any case, the last try to get the House of Stuart back to the throne had utterly failed. Bonnie Prince Charlie could not be caught – despite a huge bounty of 30,000 £ on his head – but fled to France, had numerous affairs, became an alcoholic and died as “Count of Albany” in 1788 in Rome, where he had been born 67 years ago.

According to John Prebble in his book “Culloden” (1961), the British soldiers in the battle viewed the Jacobite army with “no more kinship than an officer of Victoria’s army would later feel when surveying a Zulu Impi“. As Peter Watkins in his 1964 film sought to draw parallels with the Culloden battle and American atrocities in Vietnam, the artist, who first visited Culloden battlefield as a child, creates an installation in the manner of the Colonial Exhibition of the 19th Century, where “exotic” or “primitive people” were exhibited for the entertainment of “civilised” European audiences.

Andrew Gilbert: “Colonial Exhibition – Culloden 1746”

27 October – 7 December 2012

Opening: 26 October 2012, 1900h

Power Galerie

Hopfensack 14

D-20457 Hamburg

Germany